Today, Crister has an energetic Working Cocker Spaniel called Tøys who he’s training to become a service dog in special searches. Tøys competes in obedience trials – but takes part in everything, both summer and winter, going on hikes, bike trips, skiing and other adventures – a real “traildog”.

Crister has done his research, reading and consulting several vets to make sure that the facts in this article are, professionally speaking, on the money.

The guidance and advice here will be worth its weight in gold if your dog’s ever unfortunate enough to need it.t.

Daily check-ups

In our article about heading out into the wilds with a dog, we’ve already touched on some essential things to think about. Daily check-ups are described in detail there, but it’s worth mentioning again. Knowing our dogs as well as we do, we’re best placed to detect early signs of any alteration in their general condition. If minor injuries and other issues are detected in time, we can prevent them from developing into something worse.

All conscientious dog owners know that the most important responsibility we have is to ensure that the dog receives the necessary care and nutrition; injury and illness are part of this care. Of course, our dogs must be trained, and their lives and experiences must be good and positive – but first and foremost we must cover their most elementary needs.

This means, of course, spending enough time with them to know the very moment it’s time for grooming or a visit to the doctor.

Dyrelegehjelpen.no has made a nice video available here. Indispensable knowledge for a daily dog inspection! Worth learning Norwegian for. Me, I strive to carry out at least one complete dog-check a day. If I’ve been out training Tøys, chances are we’ve been searching in some old building or boat or woodshed where there might be things that could harm him. I’m careful to clear away nails, glass and other things that he could injure himself on – but you can never be 100% sure.

A healthy, fit, dog is attentive and active. It has shiny fur, clean ears and clear eyes. The faeces are firm, wormless, and arrive fresh every day. (Do poke a stick in the poo once in a while – then you’ll quickly see if there are worms or other things you need to do something about..!)

How to do a daily check (Norwegian)

Things to pay special attention to:

Fur

All dogs need their fur looking after: a regular brushing is required, even more frequently during shedding periods. Long-haired dogs can develop tangles and matting, or felting, in their fur. This isn’t great. Unattended to, these can cause sore, irritated and inflamed skin. Wet, matted and tangled fur are often the root cause of wet eczema.

Between the belly and the legs, behind the ears, and where the collar and harness come into contact with the fur are typical places for felting.

Most dogs are probably best off without clothes. But dogs with thin fur might have to have a jacket for protection against cold, rain and wind….

Claws

Claws should be kept relatively short. Long claws crack, break and chip more easily, and claw damage is something none of us want. Cut claws with good claw clippers. And I specify “good” here because there are plenty of bad ones out there to make the job unnecessarily difficult.

If you reward the dog after clipping the claws, this makes the whole thing more pleasurable. Actually, here’s a crucial tip: husbandry training and positive reinforcement! The first time you do it, you may want to ask the vet to show you how. Here’s a good how-to-clip video.

Teeth

Healthy teeth and gums are crucial for your dog’s well-being. Worn teeth, inflammation, tartar or gum problems are painful and must be treated. You can brush the teeth, but personally I prefer to have a good stock of Dentastix and chewing bones, both for training, so that Tøys has strong teeth and jaws, and because it works as a toothbrush, keeping teeth clean.

Eyes and ears

Make sure the eyes are clear and clean. The ears shouldn’t be dirty. Nor should they smell bad or look irritated. Breeds with drooping ears like Tøys’s are particularly prone to ear infections, which can flare up in no time. So I’m careful to dry his ears well. He’s become used to having his ears “turned” and aired after bathing and washing. Some people actually use clothes pegs and stand the ears upright together and let some air in – it’s fine with a little training on the dog’s part and isn’t harmful to the dog.

Signs of illness

As we’ve seen, a dog’s owners are best placed to detect if something’s wrong. Unusual behaviour is often the first sign that a dog’s in pain or discomfort. Signs of a dog’s in pain can include sudden aggression or irritability, a reduced appetite or low spirits. It might not meet you at the door when you come home, or becomes less active, perhaps.

General condition

Being able to give your dog first aid can be the difference between life and death. So how can you provide life-saving first aid and prevent its condition from worsening?

To recognise how a sick dog behaves, you need to know how a healthy dog looks and functions.

Pulse – what is a dog’s heart rate?

A normal adult dog has a heart rate of between 70–130 beats per minute. It’s easiest to count your dog’s heart beats in 15 seconds and then multiply that by four.

The hearts of large and older dogs beat more slowly than smaller and younger dogs. Puppies and very young dogs can have a pulse of 200 beats per minute. A scared and stressed dog will also have a faster pulse.

You can check your dog’s pulse in the left ‘armpit’ with the dog lying on its right side – if you lift the left ‘elbow’ slightly you can slip your hand into the spot.

The easiest place to find the dog’s pulse is in the depression at the far back of the belly – in the groin, if you like. The most important thing is to confirm that the dog’s heart beats approximately the ‘correct’ number of beats per minute and that the heartbeat is stron.

Breathing – normal breathing for a dog

A normal adult dog takes 8–20 breaths per minute and a young dog up to 30. It should be as easy for the dog to breathe in as it is to breathe out. If the dog struggles with either inhaling or exhaling, it may be a sign that something has become stuck in the throat or trachea. A dog that belly-breathes (stomach-breathing) after an accident may have suffered internal bleeding. Muffled breathing sounds and wheezing are also typical signs of internal bleeding. Listen and observe carefully how the dog breathes.Mucous membranes – what colour are the gums?

The mucous membranes in the mouth (gums), or around the eyes can give clear indications of how the dog is feeling.

Whether in the mouth or the eye, a dog’s mucous membranes should normally be salmon pink. Some dogs have perfectly normal spots of black or brown pigment; concentrate on the pink areas. If the mucous membranes are red, this can be a sign of stress or infection. Pale and almost white mucous membranes can indicate internal bleeding or serious dehydration. Certain poisonings can also cause a black stripe in the gums (but, of course, make sure of your dog’s baseline in terms of pigmented on the gums).

If the mucous membranes in the mouth feel sticky, it may be a sign that the dog is dehydrated. In this case, you should also do a capillary test on the dog’s skin. Lift a fold of skin up and away from the dog. Watch when you release it. The skin should quickly return to its original state. If it stays put or returns to its shape very slowly, it’s a sign that the dog may be dehydrated.

Similarly, it can be very useful to see how the gums regain their colour after pressure. Gently press your finger against the gum and check that the colour returns within three seconds. If it doesn’t, you should contact your vet.

Body temperatur

A dog’s normal temperature is between 37.5° and 39° centigrade (99.5° – 102.2° F). The temperature can be measured with an ordinary thermometer in the rectum. A young and active dog’s temperature in the high range – even a little higher.

On very hot days, a dog’s body temperature can reach 40° without it necessarily having a fever. Higher than this, though, is a red flag.

As I said, the dog’s temperature should be taken in the rectum. Ideally this should be done in the morning, or when the dog has rested for at least 20 minutes.

If you suspect that your dog is in pain or is ill, you should contact a vet immediately for advice.

Otherwise, the first thing you should check when you go on a trip, stay anywhere for a while, or move somewhere new is where the nearest vet is. I also make sure to have the number of the nearest clinic saved on my phone. It’s easy enough to find online, but it’ll save a lot of time if you run into a dog-related crisis.

In what we’ve already written about taking a dog out into the backcountry, we’ve also written the following:

Before winter really sets in, and definitely before you set out on an expedition, consider taking your dog to the vet. Make sure all vaccinations are done and the dog’s in condition. Check for parasites. It’s essential that the dog’s protected against kennel cough: this can lead to far more serious problems in the wilds.

EMERGENCY FIRST AID:

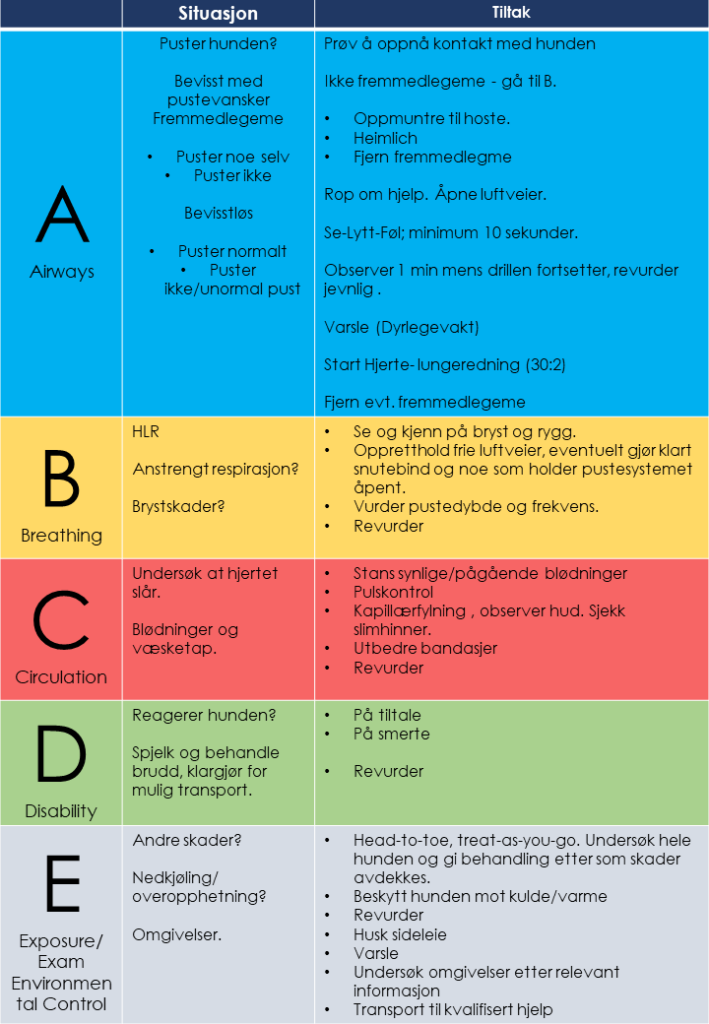

In general, give first aid to dogs according the same drill you use for humans: the “ABCDE drill”. Check for a clear airway, cardiovascular function and injuries in the order set by ABCD.

It’s a familiar drill for many. But for dogs it goes as follows:

A-B-C-D-E drill for dogs

A – Airways

B – Breathing

C – Circulation

D – Disabilities (consciousness, joints)

E – Exposure/environment (overview and protection; warmth)

The principle “head to toe, treat as you go” is followed at every single point. This includes ensuring a free airway, checking for blood/blood clots and that the blood system is working and treating injuries in the order set by ABCD.

A – Airways

Make sure airways are free. If the dog isn’t breathing, look for a bluish tongue and bloodshot eyes.

Remove any foreign bodies from the mouth and throat. If you don’t find anything, shake the dog vigorously up and down with its head towards the ground. The Heimlich manoeuvre is an option. Attempt to find help.

CPR –Small dogs

1. Lay the dog on its right side. 2. Place a hand over the dog’s heart – where the the tip of the elbow meets the chest. Lay your other hand on top on the first hand. 3. Compress the chest by pressing your hands. 4. Press approx. 30 times at a rate of 100–120 compressions/minute (try to keep the tempo to the song “Stayin’ Alive” – this gives 120 compressions/min). 5. Then blow twice into the animal’s nose. Stretch the dog’s neck, cover the nose with your mouth and blow in air until the chest rises. Remember not to blow too much air into small lungs. Repeat.

CPR: medium to large dogs

1. Lay the dog on its right side. 2. Kneel behind the dog’s back. Place your hands slightly behind and above the heart. 3. Press down on the chest with straight arms. Press hard – but try not to break the ribs. 4. Press approx. 30 times at a rate of 100–120 compressions/minute (try to keep the tempo to the song “Stayin’ Alive” – this gives 120 compressions/min). 5. Then blow twice into the animal’s nose. Stretch the dog’s neck, cover the nose with your mouth and blow in air until the chest rises. Repeat.

B – Breathing

Observe breathing. Look, listen and feel the chest. Look and feel for chest injuries, damaged ribs. Listen for breathing irregularities. Maintain a clear airway.

C – Circulation

Treat heavy bleeding as best you can. Check the pulse. A normal, adult dog has a heart rate of between 70–130 beats per minute. You can calculate how many beats there are in 15 seconds and then multiply this by four). Puppies and very young dogs can have a heart rate of 200 beats per minute. A scared and stressed dog also has a faster frequency.

The easiest place to find the dog’s pulse is in the groin, at the depression at the back of the belly. The most important thing is to confirm that the dog has a pulse, and that the heart is beating ‘correctly’.

The skin-fold test is useful: you can check the degree of capillary filling by observing how quickly a fold of skin snaps back into place. Also check mucous membranes.

Improve all bandages if necessary.

D – Disabilities (brain function)

Is the dog responsive? Check whether the dog reacts to stimulus. Splint and treat obvious fractures or limbs at abnormal angles. Stabilize injuries for possible transport to veterinary care. Stop bleeding, splint legs, etc. Keep the muzzle closed.

E – Exposure/environment

Does the dog have other injuries? Is it too cold, or too hot? Alter the dog’s environment to the benefit of its recovery. The “head to toe – treat as you go” principle applies here. Examine the whole dog and treat injuries as they are discovered. Always keep an eye on pulse and respiration.

Protect the dog from heat or cold. Wrap it in a blanket or cool it down with a wet towel. Ask yourself if another of the other steps detailed above are required.

Place the dog on its side and ensure that the airways are open. Call for help, if you haven’t done so before. Examine the surroundings for relevant information – signs of something toxic the dog may have eaten, the proximity of vehicles, etc.

Then get to the vet, as quickly and safely as you can.

TREATMENT OF INJURIES

Cuts:

For small wounds and cuts, clean the wound with Pyrisept or medical saline, both of which can be bought at the pharmacy. The most important thing is to rinse the wound well. If you do not have these products, you can boil a litre of water with 9g of salt and cool it down before use. This will be roughly the same as the salt water you get from the pharmacy.

For smaller cuts, “blood stops”, the kind you use when clipping claws, can also work. Always bandage the cut, no matter what, to protect against infection.

Pad cuts, or cuts on the paws and legs, are most common. If the wound breaks more than a centimetre, it almost always has to be stitched. Tissue can die if not sutured within eight hours. Get to the vet as soon as you can. The sooner the better. Whatever the type of cut, under no circumstances sew this yourself without the the practiced skill. It can make the injury worse.

A bit of gauze and sports tape, or possibly an elastic dog bandage, help a lot when dressing the wound. I always have a pair of paw socks with me in the dog’s first aid kit; these keep wounds clean.

If a cut’s bleeding profusely, put pressure on the wound. Preferably maintain pressure with a piece of cloth, a belt, or similar, to maintain pressure. It may be necessary to keep pressure on the wound for a long time to stop the bleeding. Get to the vet as soon as possible!

Pulsating bleeding:

If your dog is bleeding in spurts, this is because an artery has been hit.

Put pressure on the wound. Maintain pressure with a piece of cloth, a belt, or the leash. It may be necessary to continue holding the pressure. Get to the vet as soon as possible! In severe cases, you may also have to continue to apply pressure to the bleeding wound with two fingers.

Pressure bandage:

Before applying a pressure bandage, you must secure, hold, and preferably muzzle the dog. Then you can use a hard-rolled compress, or whatever you have on hand, against the wound to apply pressure until the bleeding stops. Put bandages around the wound to keep the pressure.

The bandage should be so tight that it stops the bleeding but not the blood supply. It is important to loosen the bandage regularly, preferably every 15 minutes, and at least every 30 minutes. If the wound is still bleeding, you must re-bandage it, keeping constant pressure on it if you can. Keep the body part elevated. And get to the vet as fast as possible

ør man legger på en trykkbandasje må man sikre, holde fast og gjerne snutebinde hunden. Så kan en bruke en hardt rullet kompress, enkeltmannspakke – eller det man har for hånd mot såret og trykke til blødningen stopper. Bandasjer så rundt såret og hold presset.

Fractures:

Fractures can be tricky. I have experienced this myself with my own dog. Dogs are very good at compensating for pain, so it can be difficult to detect injured toes or the like. But if you do a proper check, and feel all the bones, it’s easy to spot. Dogs usually push off with their paws if you extend their legs and push them on the pads, so if they don’t, there is at least a chance of muscle or joint damage.

The first thing to do is to check whether the break is open to the air or internal. If the dog has an open fracture, you must also check whether the wound is dirty and, if necessary, clean it as described above. If there’s a lot of contamination in the wound, it can be washed with fresh water if nothing else is available.

If you have nothing better to hand, you can fill a bag with water and then cut a small hole in one corner. If It’s still best to use salt water in a sprayer or a bottle with a spout.

Regardless, the break must be splinted to keep it stable. A dog with a broken leg must move as little as possible and must be carried. It’s therefore beneficial that your dog is used to being carried and handled.

Poisoning:

It is not always easy to see what’s lurking in the bushes, grass and undergrowth. In Norway, vipers are a common cause of poisoning – but this isn’t the only way dogs can be poisoned. Unbaked dough, chocolate, household chemicals and poisonous plants are other common causes of poisoning in dogs. According to the vets I spoke to when I wrote this, it is certainly not unheard of for dogs to arrive at the clinic after drinking antifreeze or strong detergents intended for cars and boats.

Much of this can be prevented. The best prevention, of course, is to keep poisonous substances away from dogs. Put it away in a cupboard, or high out of reach. And keep the dog away when you need to fill antifreeze or wash the car.

If you’re concerned about possible poisoning, you should always call a vet or the poison information centre. In Norway, the number’s 22591300. Make sure you have any packaging to hand, so that you can give further information to the vet or the poison information centre.

Viper bite:

Should your dog be bitten by a viper, keep it still as possible – hinder the spread of blood through the circulatory system. Then get the dog to the vet is quickly as you possibly can. Carry it if you have to.

If you have a large scarf, a tarp, or a length of fabric large enough, you can make a large cylinder or a “hammock” for the dog and tie it behind your neck. Then you can carry the dog on your belly for a good distance.

If you’re a long way from a vet, you might consider cortisone tablets. Treatment with cortisone is somewhat controversial. But in the event of bites to the head and neck, cortisone can help to reduce swelling, allowing the dog to breathe.

Insect bites and allergic reactions:

Dogs are usually stung, typically by wasps, on the face and head. If swelling occurs, it can be treated with cortisone tablets. This is usually effective. Otherwise treat them as you would a normal insect bite on a humans. And contact a vet if you’re concerned..

Drowning:

As mentioned elsewhere, dogs should always have a life jacket. Dogs being dogs, however, accidents are always possible. A little knowledge of emergency first aid can save a dog’s life from drowning.

To rid the lungs of water lungs, lift the dog by its hind legs and tap it on the chest. Get help if you can’t manage this alone.

If the dog’s been in cold water, ensure that it doesn’t get any colder. Warming a dog too quickly can cause shock. Wrap it up in a blanket, with a hot water bottle or something else you have to hand.

Shock:

Symptoms of shock are pale mucous membranes, increased heart and breathing rate, an erratic pulse and cold paws. If you have concerns, contact a vet. If you’re sure the dog’s in shock, get to the vet as soon as possible. If the dog’s conscious and responding, it’s recommended to give it fluids.

Twisted stomach/stomach expansion:

Stomach-twisting is something I’ve seen happen a few times. Most times everything’s been all right, thanks to quick treatment at the vet – but I’ve also seen it occur at night, without it being noticed.

A twisted stomach is life-threatening. It’s perhaps the worst situation I have experienced with the dogs I’ve known. It most often affects large dogs, often dogs with a deep, marked, belly. When it occurs, the stomach rotates on its own axis; this stops the supply of blood supply to vital organs and causes a life-threatening state of shock. While the cause of this phenomenon hasn’t been definitively established, it’s believed that it may be linked to overeating, food fermenting in the stomach, excessive swallowing of air, or vigorous exercise immediately after feeding. The symptoms come on quickly.

The most common symptoms are:

- Distress

- Retching without vomiting

- Swelling in the front part of the abdomen/back part of the chest

- Weakness, weak pulse, shock, breathing problems

- Gasping for breath; struggling with pain

The best, and really the only option with a very good outcome, is to get medical help as soon as possible. Treating this yourself is very complicated and rarely goes well.

If it’s impossible to get to the vet, the stomach must be punctured. The stomach resembles an inflated balloon. It should be punctured by inserting something thin and sharp, such as a needle, where it’s largest on the right side, behind the last rib. It’s very important that you don’t penetrate the left side of the dog: the heart and other important organs are located there.

While a sterile needle is best, the priority is the dog’s immediate state, so here it’s important to act, quickly, with what you have. This is, of course, a last resort. If you find yourself having to do this, get to the vet as quickly as you possibly can.

The only reason I’m explaining this here is because many reading this will be far off the beaten track with their dog in a crisis. Help can be a very long way away.

Eye injuries:

Symptoms of eye injuries are: watery or red eyes, squinting, frequent blinking or alterations/ differences in the pupils. The overproduction of gunk in the corner of the eye can also be a sign of eye damage.

All eye injuries should be taken seriously and examined by a vet. If only a single eye is affected, it’s often more serious than symptoms in a single eye – but this isn’t a hard and fast rule.

Cleaning and rinsing the eye is the initial treatment. Also ensure that the dog can’t make it works by scratching its eye – a collar might be a good solution.

REMEMBER! Dogs can be affected by strong sun and snow blindness. Long periods of strong wind can also be an issue. There are both ski goggles (Doggles) and sunglasses for dogs. Norwegian rescue dogs, the Armed Forces and the Police use glasses like these for many different purposes on their service dogs – for good reasons.

Claw injuries:

If the dog damages or breaks its claws, this can creates trouble and serious discomfort. There isn’t much that can be done about it apart from disinfecting and protecting the injury. Cotton wool between the toes, a bandage around the paw and an elastic bandage make for good protection. A paw sock is recommended too. In case of broken claws or toes, you should always visit the vet.

Wet Eczema:

Wet eczema, also known as “hot-spot”, is a fairly common condition for dogs. It’s an acute, if comparatively superficial and localised, infection of the skin. Moist eczema most often appears as a sticky, tender area of the skin. Fur is commonly matted. The dog’s skin will be red and irritated and sticky in the infected area. Moist eczema often flares up overnight; it is, at least, itchy; at worst it is painful. Typical areas for mooist eczema are the cheeks, neck and shoulders, the back, thighs and base of the tail.

While such infections can affect all dog breeds, they’re most common in dogs with long or thick fur. Dense, tangled and damp fur is often a breeding ground for moist eczema.

Wet eczema can be caused by parasites such as fleas, lice and mites. Allergies or dense, long, damp and ungroomed fur can also be common underlying causes.

The easiest thing you can do to prevent moist eczema is to keep the coat well-groomed, dry, and free of tangles. A flea comb’s recommended, and make sure that the dog’s not bothered by fleas, lice or ticks. Moist eczema can also arise from small wounds. These should be treated as soon as possible to avoid flare-ups.

If wet eczema’s treated early, it can be stopped. The inflammation can be reduced by shaving the fur where the problem is, washing with a dilute solution of chlorhexidine, and then covering the wound.

A vet should be contacted if the infection spreads or the dog’s in significant pain. Moist eczema can be very painful for dogs; it’s not uncommon for a sedative to be given before shaving and treatment.

If moist eczema reoccurs persistently, the underlying cause should be investigated.

Uterine inflammation and urinary tract infection:

Symptoms:

- Often occurs a few weeks after the dog’s been in heat

- Increased thirst

- Increased urination

- Decreased appetite

- Vomiting

- Lethargy

- Discharge (not present in case of “closed” uterine inflammation)

Consult a veterinarian. The dog probably needs antibiotics and treatment. http://video.tu.no/k9-heromov

SOURCES

Tryggers, Y. (2010). Førstehjelp – når ulykken er ute. Häftad, Svenska: Canis Academy AB

Stai, M. Dyreklinikk.no – Dyrelegehjelpen, for veterinærer. Dyrlegehjelpen – oppslagsverk. Hentet fra Dyrelegehjelpen, Veterinær og: https://www.dyreklinikk.no/tags/dyrlegehjelpen/

AniCura Norge, Anicura Group. Førstehjelp på hund. Hentet fra:https://www.anicura.no/fakta-og-rad/hund/forstehjelp-pa-hund/

Dahl, S., Hønefoss Dyrehospital. Førstehjelp. Hentet fra: https://www.dyrehospital.no/dyreforum/helsebiblioteket/forstehjelp

See. A. (2011). Perth Vet Emergencies – First Aid Book. A Common Guide To Pet Emergencies. English: Perth Vet Emergency; Perth, Astralia.

Dyreklinikk.no – Landets dyreklinikker på nett. Helse og sykdom. Hentet fra: https://www.dyreklinikk.no/stell-av-kjaeledyr/hund/helse-og-sykdom/

Martell S. Agria Dyreforsikring (14 juni 2013). Førstehjelp for hund. Hentet fra: https://www.agria.no/hund/artikkel/sykdommer-og-skader/forste-hjelp-for-hund/

Monteiro, M. (2011). The Safe Dog Handbook: A Complete Guide to Protecting Your Pooch, Indoors and Out. English, Los Angeles, USA: Crestline.

American Red Cross (2018). Cat and dog Firs Aid [Online Course]. English: American Red Cross.

Norsk Kennel Klubb, Norges Veterinærhøgskole & Smådyrpraktiserende veterinærers forening. Nøkkelen til førstehjelp? – Hefte.

Norsk Kennelklubb og Agria Dyreforsikring. Hurtiguide – hefte.

Norsk Kennelklubb. Helse. Hentet fra: https://www.nkk.no/for-hundeeiere/helse/

Mattilsynet (16.04.2019). Dyr og dyrehold. Hentet fra: https://www.mattilsynet.no/dyr_og_dyrehold/

Ølberg, H. Aktia. Førstehjelp for hund – PDF. Hentet fra: http://www.akita.no/SU/Foerstehjelp%20for%20hund.pdf

Forsvarets Hundeskole

Hestavangen Dyreklinikk

Livgardets Hundtjänstenhet

Handling hypothermia

Do you know what to do when you’re faced with someone dangerously cold? Command of the basic facts can be lifesaving – and this is just as relevant for us those of us who hit the mountains for the joy of it as it is for guide and members of the rescue services.

Seven tips to find a safe route up the mountain

Here are some simple, concrete, tips on how to find the safest route up a mountain on skis. Some things in life are necessary. Some things aren’t necessarily easy. But, as every skier knows, the only thing that really matters is skiing as much as humanly possible – so getting these down is a question of making life worth living.

Firing up the stove in winter

Nothing whets the appetite more than a long day skiing in the winter mountains. Fire up the burner, boil some water for some tea and reach for the packet of dehydrated chilli: paradise found. But doing this in the winter you need to bear a couple of things in mind. So here are some wily strategies to make things easy and safe.

So – what exactly is a skin, anyway?

Skins are more than a strip of carpet with glue on the back. They’re tools designed to help us in pursuit of pristine snow, perfect lines, and/or solitude. Something this magical demands a proper description of how it’s made.

The dog’s mountain code

Norwegian vets say that holiday periods mean more enquiries. The Åsnes Academy has excellent articles on care for your dog in the mountains, including first aid. Here, however, we’ve chosen to put together what we call “the dog’s mountain code” – with some very specific tips for things like the Easter holiday.

Eight reasons to take a course in avalanche rescue

Avalanche rescue is an essential skill, required by all of us who visit avalanche terrain. No one wants to have to use these skills – but if you ever need them, you need to have them down. True, the most important thing is to avoid being in an avalanche in the first place. But if something were to happen, every second counts. And this means training.