What are rocker, nordic rocker, taper and sidecut?

You may know these things change the lines of your skis when you pressure them.

If you’re wondering how and why, then read on..!ROCKER

Why rocker?

Think of a rocking chair’s rockers. When we talk about rocker in skis, we have this shape in mind. When the ski industry first started turned to rockered skis, it was for manoeuvrability and float in wide alpine skis. With the tip lifted from the snow and a shorter effective edge, skiers could use their weight more constructively, initiating turns with more control and less force. Initially, rocker was relatively aggressive –think banana skis or water skis. The introduction of rocker made powder snow much easier to navigate.

Over the last decade or so, we’ve seen rocker introduced to most types of skis – even to cross-country skis built for the backcountry.

Nordisk Rocker

The term “nordic rocker” was introduced by Åsnes when we started producing skis with a rocker profile adapted to backcountry cross-country skis and nordic skis for polar conditions.

When you hold skis with nordic rocker sole to sole, they basically look like a normal cross-country ski. The tips of the skis touch each other as you’d expect. When you put pressure on the skis, however, the magic of the nordic rocker emerges. When the ski is loaded, the tips of the skis lift, revealing the rocker. Suddenly the ski has the profile of a true rockered ski.

In deeper snow, the nordic rocker helps with stability. With light pressure on the ski, the rockered tips open, ensuring the ski stays naturally on top of the snow. But the same ski will also track beautifully on more consolidated snow when you want to propel yourself across the flats. Ascents and traverses are more manageable; stability is preserved; the skis stay on top of the snow. On the descent, the tips perform the function of a classic rocker; even more importantly, the nordic rocker makes the initiation of turns much easier. Further, the ski “eats” more of the surface, preventing hooking in difficult conditions and making the downhills easier. Using Nordisk Rocker allows you to have less sidecut in the ski. This gives a longer turning radius, but affords a cross-country BC ski that works well both for distance and downhill.

Rocker + Camber

Combination of rocker and camber

Rocker is very often combined with camber for the sake of versatility. Typically, such a ski will have rocker in one or both of the tips and a tensioned wooden core, the camber arched in the midsection. A combination like this makes for a ski that both floats well in deeper snow and offers a responsive, propulsive “pop” in its contact with the snow while making good turns on hard surfaces. The camber’s height, of course, decides the size of the ski’s wax pocket.

Rocker also offers a larger contact surface at speed and when the skis are on edge. This means we can make wider skis behave on hard surfaces in a way that only narrower skis did before.

Confusingly, different ski manufacturers use different terms for rocker: “early rise” and “reverse camber” are two. The principle’s basically the same. In some cases, the term “reverse camber” denotes skis with rocker throughout the length of the ski. This means that the ski doesn’t have a normal/traditional camber in the midsection but is formed with an upward bend something like a banana.

Different types of rocker

Rockered front tip (most common)

Most carving skis and alpine touring skis, and now even a number of backcountry cross-country skis, have a rockered front tip. We even see this on alpine racing skis and narrow, lightweight cross-country racing skis. With a slightly raised front tip, the skis are easier to handle at lower speeds and easier to turn. It also prevents the front tip from hooking in the snow. When the skis get up to turning speed, it’s possible to engage the snow cleanly along the effective edge. A degree of camber in the rest of the ski ensures that the skis are directionally stable and responsive.

Rockered tip and tail

Rocker in both the front and rear tip improves float on the downhill, and on looser snow generally, and makes for a ski eager to turn. Improved manoeuvrability comes, in part, from the skier no longer having to work to lift the tips from the snow. A degree of camber in the midsection affords responsiveness and engagement at the edge. There can be a disadvantage with skis generously rockered at the tips, however – they can can be less stable at speed and track less efficiently on the flats.

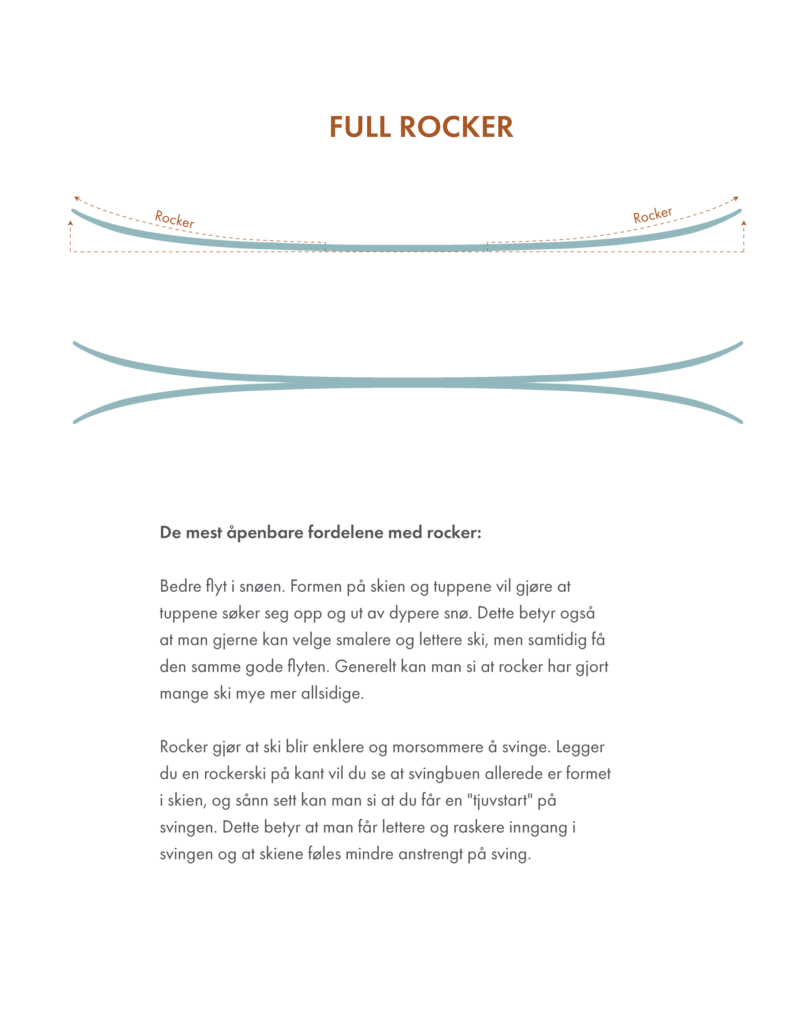

Full rocker (reversed camber)

A fully-rockered ski will have minimal or no camber. It’s a design that works well in loose conditions and offers particularly good float. The intention here is a ski that turns and edges very easily – an advantage for wide powder skis. Skis with full rocker are, however, experienced to be difficult descending in harder conditions. The lack of camber translates to less force transmitted to the edges. Fully-rockered skis are mostly made for deep snow and loose conditions; they don’t make for an efficient all-round ski.

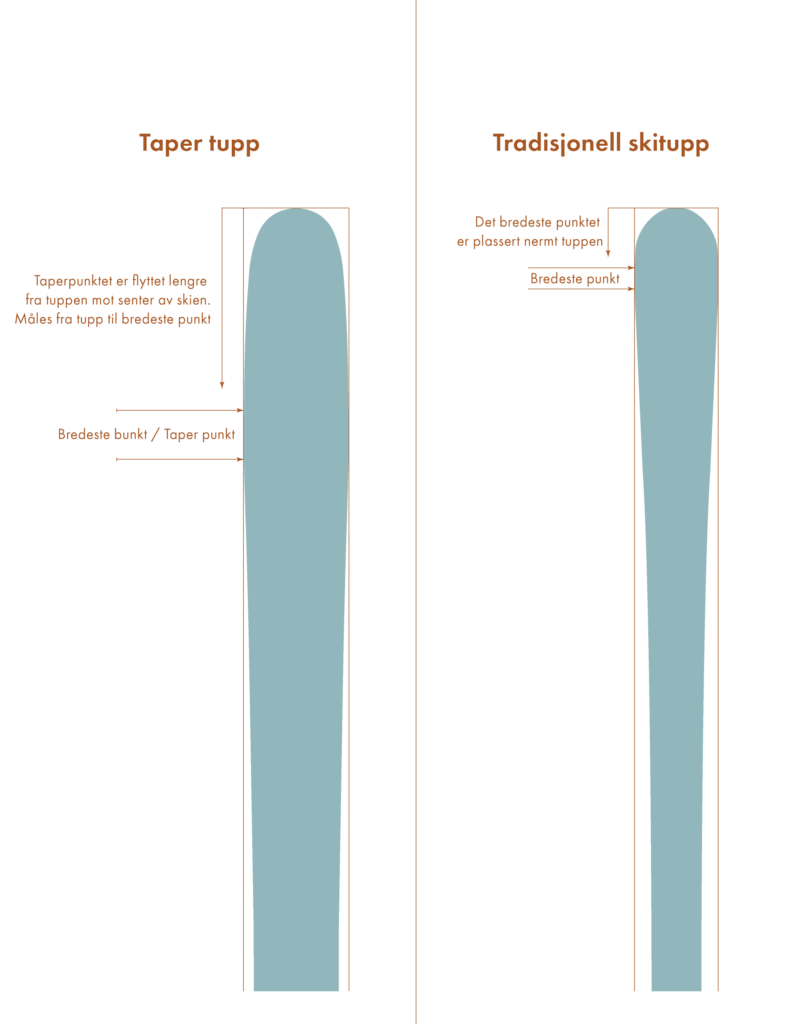

Taper

Taper, like rocker, is now a common design decision for modern skis. With a tapered ski, the widest point, usually way out at the tip, is pulled in more towards the centre.

The extent can vary. Some skis only have a few centimetres of taper; others have significantly more. Taper is most common on skis intended for turns away from groomed alpine runs. It offers a few useful advantages.

Taper prevents the tips from hooking in the snow –particularly important in fresh snow, and less-than-ideal conditions. A lot of taper makes it easier to surf sideways on high-angled powder snow; the tips are lighter, making for a more manoeuvrable ski where turns can be initiated with less force. Or sort of – taper affords the feeling of a lighter ski, even if the true weight is unaltered.

Many ski manufacturers turn to taper through a focus on making the tips as light as possible – this reduces swing weight (the force required to get a ski to pivot around the middle). On the hill, taper will make the effective sidecut shorter. A shorter effective side-cut makes for more playful skis, more willing to turn on hard surfaces. Long taper can, however, make skis somewhat less stable at speed

.

The most obvious benefits of taper:

Sidecut

Your skis are not rectangular. “Sidecut” is the amount of material “cut” from their sides. This helps to reduce the radius of your turn.

In an attempt to reduce the frequency of injuries by bring speeds down, FIS (International Ski Federation) decided to move the gates closer together in the slalom and giant slalom courses. Ski manufacturers responded by making skis with a lot of sidecut that were easier to turn. They promptly understood the mainstream sales potential of these skis.

The development of new materials and production methods has made it possible to make skis with greater sidecut while maintaining the ski’s torsional stiffness – something vital for a ski if it is engage properly on hard snow. The ski must flexible enough to “press out” the sidecut when you’re edging the ski.

Carving skis have sidecut: all skis wider at the front and back than in the middle can be considered carving skis. That term’s still mostly used for skis with a relatively large sidecut. With some exceptions, that means skis for groomed slopes. These skis, usually some 70 mm at the waist (the narrowest point of the ski), can thus be characterised by a wide tip and rear in comparison with the waist. More radical skis often have straight edges in the rear section affording extra speed out of the turn. These skis often require a little more from the rider than skis with a rounded rear section, which makes it easier to gain control out of the turn.

Radius

The deeper the sidecut, the sharper the turn.

The formula is:

cm sidecut * cm sidecur /((mm front + mm back -2 *mm wasit) *2 ) / 10 = m turning radius

The turn radius is the radius the ski turns in when viewed from above. This isn’t the same as the arc it imprints on the snow as you make your graceful descent – this depends on gradient, speed, bodyweight, the nature of the snow, the concavity or convexity of the ground, etc. It does however says a lot about how the ski will turn, and that’s useful if you need a benchmark when you’re choosing skis.

Tuning steel edges

Tuning and maintaining your steel edges is pretty simple if you have the tools. If you don’t, you can take them to a workshop to have them machined. Everyone has an opinion when it comes to grinding. And much is a matter of preference. But it’s worthwhile bearing in mind that ski designers made their decisions for a reason…

Choosing bindings for cross-country BC skis

Not certain which bindings choose for cross-country skiing in the backcounty? Confused by the difference between NNN-BC or 75mm bindings? Cable-curious? Find all the answers here!

So – what exactly is a skin, anyway?

Skins are more than a strip of carpet with glue on the back. They’re tools designed to help us in pursuit of pristine snow, perfect lines, and/or solitude. Something this magical demands a proper description of how it’s made.

Choosing the right skin

Short skins have revolutionised trips to the backcountry on nordic skis. Long skins get you to the top. You can nail gliding, climbing, pulling, gripping, poor conditions, good conditions, days when you’re feeling too lazy to wax. We break down material, length, width, care, and everything else you’ll want to know.

Understanding sidewalls

Sidewalls. All skis have them. Few of us know what they actually do. Join us as we explain how they affect the strength and properties of your skis.

Mounting bindings on cross-country BC skis

If you’re going to mount bindings on cross-country skis built for breaking trail, you have a choice. You can let professionals do it for you and avoid water damage to the wooden core, screws sitting proud of the holes or crooked bindings… or you can bid farewell to your warranty cover, prepare the polyurethane glue and drill, and read on…