What’s in a skin?

1. A directional plush

«Vurder bruk, behov, fysisk form og teknikk når du velger hvilken fell og hvilket materiale du skal ha i din fell. Hvis du er en vanlig skiturist eller legger ut på langturer, kan du med fordel velge en fell som er lettere og som gir god glid. Hvis du bare sporadisk går på ski eller er ny i sporten, kan du spare penger og velge en nylonfell for deres holdbarhet og utmerkede grep.

The surface in contact with the snow is a plush material. The nature of the plush determines the skin’s capacity to grip and glide. These properties vary depending on the material used (nylon, mohair, or blend) and how the fibres are woven (thicker or thinner, longer or shorter, more angled or less). As a general rule, skins that glide well have a slightly weaker grip, and vice versa.

The composition of long and short hairs plays a great role in a skin’s capacity for glide. As counter-intuitive as it sounds, skins with many long hairs actually glide better. If you study sealskin, which is what all modern traps attempt to imitate, you’ll see that sealskin consists of several layers of both long and short hairs.

Mix skins, with a combination of mohair and nylon, offer a good compromise between good glide, grip, weight, durability, and price.

Life: approx. 120.000 m

Skins – the alpine tourer’s best friend!

2. Impregnation and treatment

Skins are commonly treated with various types of impregnation. A good skin has the right combination of long and short fibres and a treatment that won’t cause environmental issues. Skins are treated to ensure the best possible glide, the least uptake of melted water, and for the functioning of the fibres’ properties: grip on the backslide, glide on the forward slide.

Today, fortunately, most reputable skin-manufacturers have completely cut out the use of fluorines such as PFOA and perfluorocarbons (PFCs). Perhaps the most important treatment is to prevent skins from absorbing liquid water. This is the way to “glomming”, which eventually leads to ice-covered skins that neither grip nor glide like you want.

Glomming occurs in several ways. Wet fibres can freeze when the temperature changes. Flakes of snow attach themselves to the frozen plush, collecting more flakes of snow. Ice builds up when snow melted by friction refreezes.

Fibres are dyed, too. The arrangement and treatment of the fibres constituting a skin’s plush plays a crucial role; the density, arrangement and angles are what separate the really good skins from the less sophisticated skins.

3. Lining, backing and membrane

The lining of the skin (or “backing” as some call it) is often made of a textile like cotton. This is the foundation and anchor of the skin’s fibres.

The lining also functions as a membrane; in some cases the cotton weave is also combined with a rubber membrane to prevent water penetrating through the plush material in contact with the snow and damaging the glue. If the glue’s exposed to a lot of moisture, it dissolves or gets leached away; obviously, this is an issue for a skin primarily attached by adhesive. Good skins have treated layers and resistance to saturation.

4. Glue or adhesive coating

All skins have some form of adhesive on the face lying against the base. This is essential if the skin is to stay firmly attached.

Experience from manufacturers and those most active in the mountains tells us that a skin with a good HotMelt glue works best. Cold and wet conditions are challenging for good adhesion between ski and skin. The right glue, in the right quantity, is crucial. In general, a skin sticks to the ski better when temperatures are slightly warmer than when it’s cold or very wet.

There are skins with a coating of silicone or other hydrophobic substances. But the vast majority of skins use a good glue and seek to solve the issue of saturation through various means.

An avalanche course: the most valuable “gear” you can get

New gear is the best. Everyone loves gear. In fact, the only things better than gear are skiing and staying alive. To maintain this state of affairs, a knowledge of avalanches, navigation, terrain and the basic physics of snow is essential – it means the power to travel safely, on your own terms.

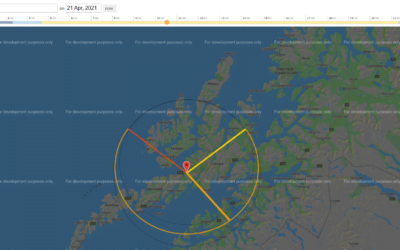

Digital tools for the ski tour

Don’t give up if your go-to spots are snowless or unskiable wastes. There could well be untouched, soft powder in them there hills! Read on to find digital tools for finding the white stuff when all hope is lost…

Myths about skins – busted

Not everything you hear about skins is right. We’re here to dish the skinny on skins, busting some misconceptions about your skins, complete with counter-evidence and tips garnered through trial and error in real snow, by real skiers, in actual Norway.

Firing up the stove in winter

Nothing whets the appetite more than a long day skiing in the winter mountains. Fire up the burner, boil some water for some tea and reach for the packet of dehydrated chilli: paradise found. But doing this in the winter you need to bear a couple of things in mind. So here are some wily strategies to make things easy and safe.

Tuning steel edges

Tuning and maintaining your steel edges is pretty simple if you have the tools. If you don’t, you can take them to a workshop to have them machined. Everyone has an opinion when it comes to grinding. And much is a matter of preference. But it’s worthwhile bearing in mind that ski designers made their decisions for a reason…

Seven tips to find a safe route up the mountain

Here are some simple, concrete, tips on how to find the safest route up a mountain on skis. Some things in life are necessary. Some things aren’t necessarily easy. But, as every skier knows, the only thing that really matters is skiing as much as humanly possible – so getting these down is a question of making life worth living.