What are sidewalls?

The sidewall is a strip of dense plastic incorporated into the ski construction. It sits between ski core and topsheet along the ski’s length, over the edges of the sole. Its primary purpose is to prevent damage to the ski core, maintaining the ski’s overall integrity. If you end up in a tangle of limbs and skis falling foul of a steep and icy snowmobile track, it’s the sidewall that prevents the steel edge of one ski from exposing the wooden core of the other along the side. Likewise, if you drop your skis on the ground or hit a stump shedding speed in a forest, the core will remain undamaged when the sidewall takes the brunt.

ABS-sidewalls

Many skis made in “sandwich” or “semi-cap” construction have ABS sidewalls. This is acrylonitrile-butadiene styrene – a type of thermoplastic that’s become the standard in good skis. It offers good stability, it protects against water penetration, and protects your sides from wear and stray steel edges. ABS sidewalls are associated with higher costs for ski manufacturers. But they add many desirable properties. Since this type of sidewall is highly strong and dense, it confers the ski torsional stiffness and better edge grip. Torsional stability is resistance to twisting and bending – a positive attribute when switching from edge to edge, initiating a turn, or edging your skis to carve or shed speed with control. Skis with ABS sidewalls have better characteristics when driven hard, on edge, than skis without. They’re also more resistant to damage, water penetration and easier to repair should you damage the steel edge – even if the skis are somewhat heavier and more expensive to produce.

ABS sidewalls. Photo: Crister Næss v/ Åsnes

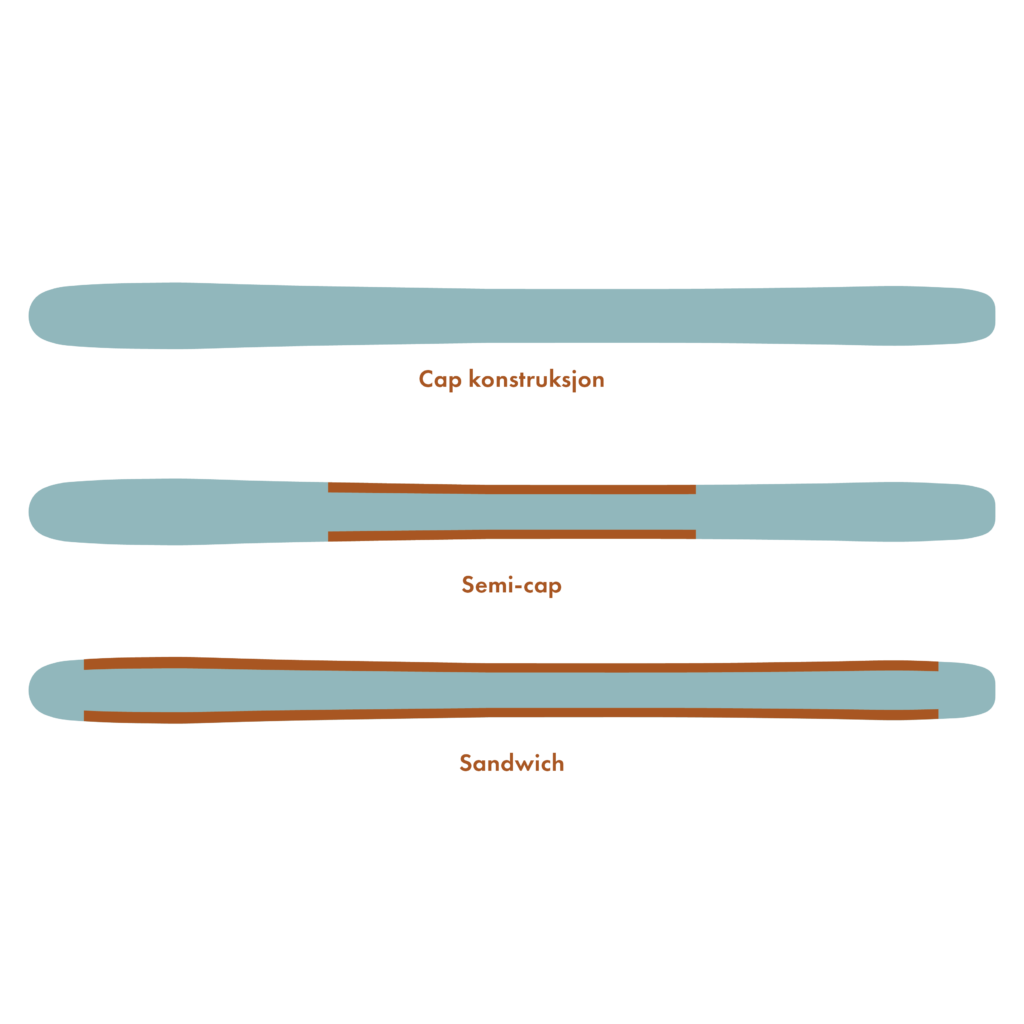

The three different kinds of sidewall construction

Today, it’s reasonable to say that factory-made skis come with three different types of sidewall construction. The difference between them is a question of how much of the ski is covered along the length. As we’ve seen, the ski’s sidewall determines its torsional rigidity – its willingness to twist and bend from edge to edge. Having a ski with high torsional stiffness is an asset when you’re edging your skis. It’s about control. A good sidewall mitigates edge compression. Imagine a dent at the edge of your base caused by, say, stomping hard on a concealed tree stump. The base of your ski is compressed in that spot, no longer flat. The dent has bent the sidewall up so far that the edge of the ski is distorted. Perhaps the topsheet has even come free. This is edge compression. It can be staved off by the density of an adequate sidewall, preventing the ski from over-bending and the core losing its integrity in that spot..

“Sandwich” construction

Skis with sandwich construction have the greatest torsional rigidity, longevity, and ruggedness. The entire sidewall is buttressed, making it hardy and resistant to twisting from edge to edge.

Cap construction

Where the sandwich construction is all about covering and buttressing along the ski’s edge, in a cap construction ski, there’s nothing there other than the topsheet . Think “marzipan on a cake” sealing the contents, in this case shrunk to the core, down along the walls to the steel edge and sole. This results in a slimmer appearance, perhaps more rounded, depending on the kind of ski.

Semi-cap construction

It probably isn’t difficult to work out what semi-cap construction entails: the design aims to exploit the advantages of both cap and sandwich with a partially-covered core buttressing the ski’s effective edge.

Rocker, nordic rocker, taper and sidecut

Reading the specs, we read about rocker, nordic rocker, taper, and sidecut. If you don’t know what these things are, or what effect they have on the properties of your skis, read on as we break it down…

Choosing bindings for cross-country BC skis

Not certain which bindings choose for cross-country skiing in the backcounty? Confused by the difference between NNN-BC or 75mm bindings? Cable-curious? Find all the answers here!

Waxless or waxable skis?

Buying new skis and not sure whether to choose waxable or waxless bases? Maybe you think grip wax is tricky. Maybe you find the convenience of waxless is enticing. Here’s your path through the pros and cons (and the science!) of both…

What are carbon skis really?

Is there really any such a thing as a “carbon ski”? Well… no. We explain why – and what carbon and fiberglass actually mean to ski construction.

Prepping and waxing cross-country skis for the backcountry – simply

When we wax cross-country BC skis, the best approach is often the simplest. If you’re in the mountains for several days, you want something that works, well enough, without fuss, for most of the day. Luckily this isn’t rocket science

Tuning steel edges

Tuning and maintaining your steel edges is pretty simple if you have the tools. If you don’t, you can take them to a workshop to have them machined. Everyone has an opinion when it comes to grinding. And much is a matter of preference. But it’s worthwhile bearing in mind that ski designers made their decisions for a reason…