Camber and stiffness

Your cross-country skis aren’t perfectly flat. They’re cambered – there’s an “arch” in the central section. Some skis have more camber than others (that is, more space between the sole at its highest point, beneath the bindings, and the ground). But there’s more to it than that. “Stiffness”, measured by the force needed to squish the grip zone against the snow, plays a role. As does the distribution of the camber along the ski’s length. These days, many cross-country skis are designed with rocker at the tip, and maybe the tail, too. Think of rocker as the reverse of camber; if you have a rockered tip, the tip will rise from the snow earlier than it would on a ski without rocker. This affects the way that a cambered ski functions. Imagine a ski on a flat, hard, surface with the sole facing down and the middle of the ski arched slightly off the snow. The two contact points often correlate with the widest parts of the tip and tail. The part of the ski between these two points is essentially the ski’s effective edge: the part of the ski in contact with the snow when the ski’s turning.

Camber: the pros and cons

The pros of camber:

The cons of camber

Measuring camber and stiffness in cross-country BC and alpine touring skis

De fleste fjellski er utviklet for optimal bærere- og flyteevne i snøen gjennom et stivt midtparti og avtagende bøyingsmotstand utover mot fram- og bakski. Gåspenn og stivt midtparti gjør at du ikke tråkker skia helt ned når du fører henne framover. Dermed blir friksjonen mot smørelommen nærmest halvert, og du sparer krefter og reduserer mekanisk slitasje på skismurning og kortfell.

I fjellski, toppturski og alpinski måler man ikke spenn på samme måte som i en klassisk langrennsski. Spennet er der for å gi skien ulike egenskaper, avhengig av tiltenkt bruksområde og ønsket kraftoverføring, mer enn for å kunne gi spesifikt utmålt smøresone. Spesielt for fjellski er at godt feste er førsteprioritet. Man må også kunne beregne inn sekk på ryggen, ferdighetsnivå, ulike bruksområder, bruk av fell og eventuelt at noen skal trekke pulk. Dette er så mange faktorer at det blir umulig å beregne spesifikke smørelommer. Målinger har tradisjonelt sett vært foretatt ved å tillegge belastning på skien, i form av kroppsvekt, for presse ned skien og måle seg fram til kontaktflaten mot underlaget. Kontaktflaten under skien med denne tilleggsbelastningen har da blitt smøresonen på skien, for det er den delen av skien vedkommende klarer å bruke med den eksakte kroppsvekten. Slik måling sier derimot bare noe om stivheten i midtpartiet i skien – spennlengden varier etter formen på skien, spennkurven til tre-kjernen og fordelingen av stivheten i skien.

Cross-country BC skis are commonly designed for efficiently bearing weight in conditions that demand “float”. The middle section is designed to be stiff; resistance to load decreases in the sections to the front and rear of the ski. The stiffness of the cambered section means that the ski isn’t flat against the snow when you want it to glide forward. This is good: friction against the wax pocket is almost halved; energy is saved and mechanical wear and tear on skis and skins is reduced.

Camber isn’t measured in cross-country BC skis and alpine touring skis in the same way it’s measured in classic “langrenn” skis built for tracks and racing. In the backcountry, the priority is grip. Camber is tuned to afford the ski specific properties; these depend on where and how the ski is intended to be used. Once you factor in a pack, pulk, skins and conditions, it’s basically impossible to calculate a specific, repeatable “grip zone”. Not so with classic langrenn skis, however, where it’s both possible and useful to discover the grip zone by loading the ski with bodyweight to flatten the camber and then seeing which surfaces are in contact with the ground and which aren’t. In this way, we can see which sections of the ski are the glide surfaces and which is the grip zone, and wax accordingly, for the skier’s specific bodyweight and the camber of the ski. This measurement, however, only tells us about the stiffness in the ski’s middle section – the length of the camber varies according to the shape of the ski, the curve of the camber impressed into the ski’s wooden core, and the way the flex alters along the ski’s length.

STIFFNESS

The way stiffness is distributed along the length of the ski is crucial for the ski’s properties

A ski’s intended use decides the appropriate combination of camber and stiffness in its design. Two skis with apparently identical camber can assume completely different lines and properties when the ski’s subjected to load and its longitudinal stiffness comes into play – that is, we can see how the load of body weight is distributed along the ski’s length.

To find the real curve of the camber, we must look at how stiffness is distributed through the ski:

Category A DOWNHILL CAMBER

If you prioritise a ski’s downhill performance, then stiff camber and a pronounced wax pocket aren’t so important. It’s desirable, instead, to shape the ski to emphasise its turnable, stable, properties; doing so, rocker and taper are appropriate design choices.

Downhill-focused skis tend to be softer in the first third, to feature rockered tips, and to be formed with a fairly low camber, assisting an even distribution of force to the steel edges. Wider cross-country skis for the backcountry tend to follow these principles (as do alpine touring skis).

High torsional stiffness of such skis (how resistant they are to “screwing” along their length) is desirable, again assisting control along the steel edgese.

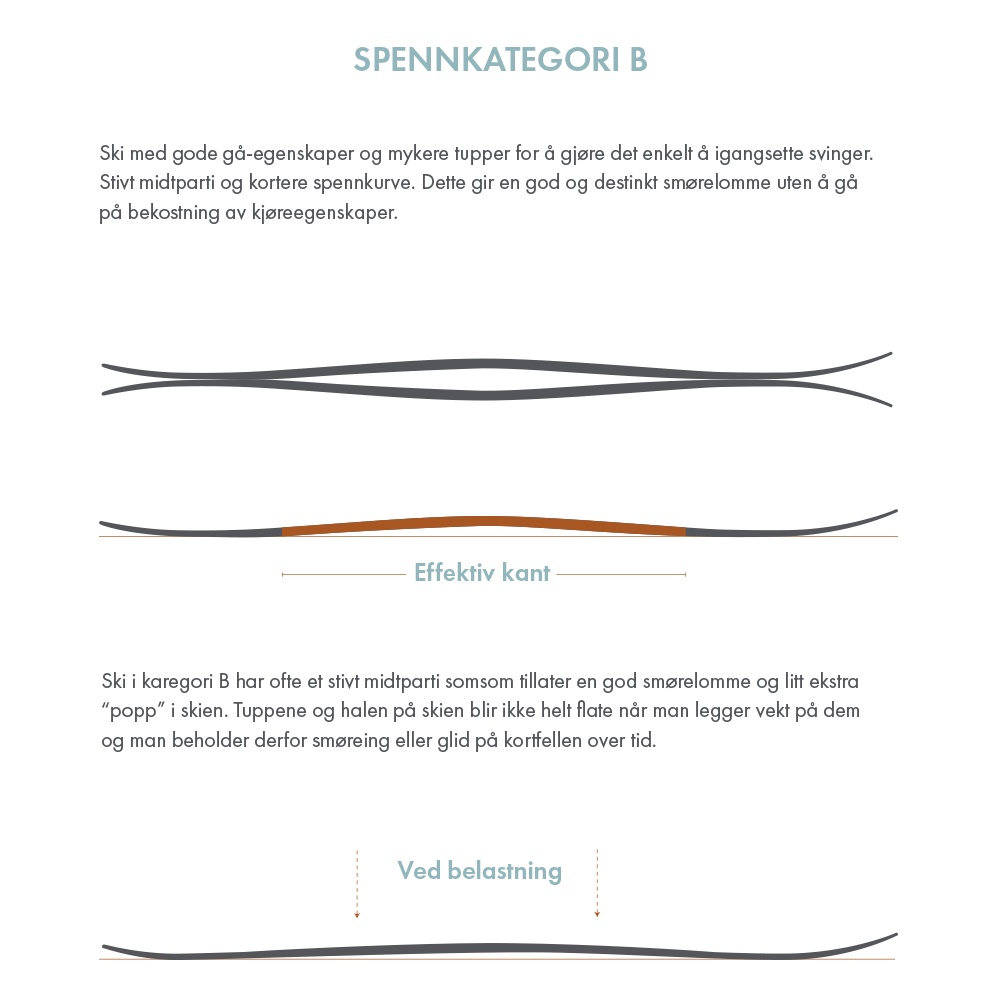

Category B ALLROUND CAMBER

If you want skis that function in a wide variety of conditions and terrain, and you’re not necessarily planning on going out with a full pack or pulk, you’re after an all–rounder: a ski with a stiff midsection, a moderately high wax pocket, and a softer flex forward and aft.

This is a ski characterised by what’s known in Norwegian as a centred gåspenn – a stiffer, central camber designed to permit more efficient forward propulsion through weight transfer, contact with the snow, and a kick-and-glide motion. It cruises nicely on the flats, but has soft tips for initiating turns and keeping the ski afloat in deeper snow.

These are perhaps the characteristics of the traditional fjellski – a cross-country ski built for use in the backcountry, somewhat playful and turnable.

Category C DISTANCE CAMBER

If you’re planning tours with heavy gear out in the wilds, where the the snow is deep and the terrain’s serious, it’s important to choose a buoyant ski with load-bearing properties.

Skis designed for carrying a load or pulling a pulk have similar properties to skis designed for efficient glide: a firm middle-section in a ski where the load can be distributed along the ski’s length as a function of longitudinal stiffness. Such skis have a prominent wax pocket, allowing grip wax to ride above the friction of the snow, so remaining in place for as long as possible.

In Norway, this kind of camber’s referred to as gåspenn – roughly “walking camber”. We usually see it in narrower cross-country BC skis built for distance and in classic “langrenn” skis built for cruising at speed on prepared tracks.

What are carbon skis really?

Is there really any such a thing as a “carbon ski”? Well… no. We explain why – and what carbon and fiberglass actually mean to ski construction.

Myths about skins – busted

Not everything you hear about skins is right. We’re here to dish the skinny on skins, busting some misconceptions about your skins, complete with counter-evidence and tips garnered through trial and error in real snow, by real skiers, in actual Norway.

So – what exactly is a skin, anyway?

Skins are more than a strip of carpet with glue on the back. They’re tools designed to help us in pursuit of pristine snow, perfect lines, and/or solitude. Something this magical demands a proper description of how it’s made.

Tailoring long skins for alpine touring

Wondering how to tailor your skins for alpine touring? Here’s an overview – care and trimming long skins for touring skis.

Choosing bindings for cross-country BC skis

Not certain which bindings choose for cross-country skiing in the backcounty? Confused by the difference between NNN-BC or 75mm bindings? Cable-curious? Find all the answers here!

Rocker, nordic rocker, taper and sidecut

Reading the specs, we read about rocker, nordic rocker, taper, and sidecut. If you don’t know what these things are, or what effect they have on the properties of your skis, read on as we break it down…